A young Temiar girl.

A young Temiar girl.

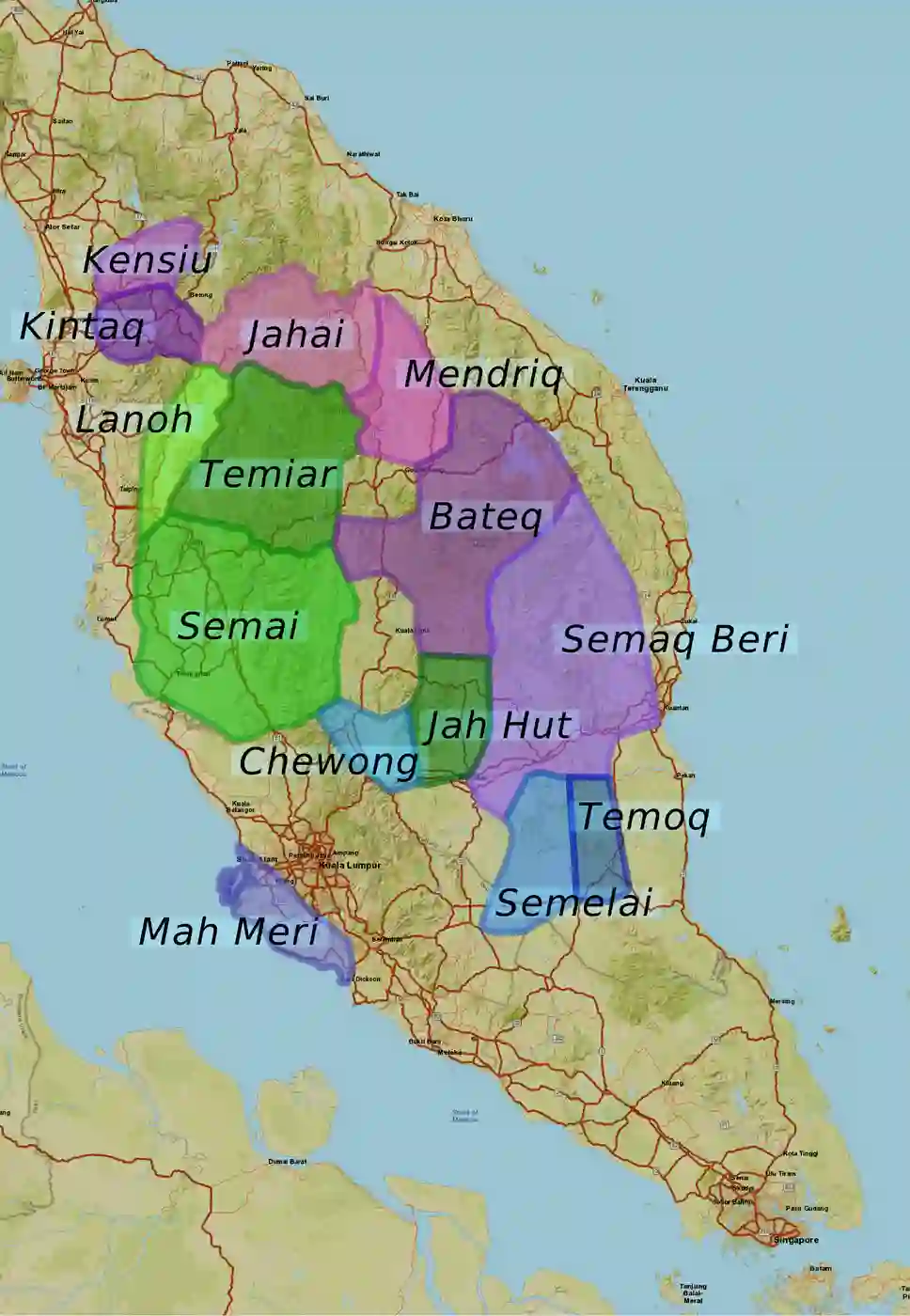

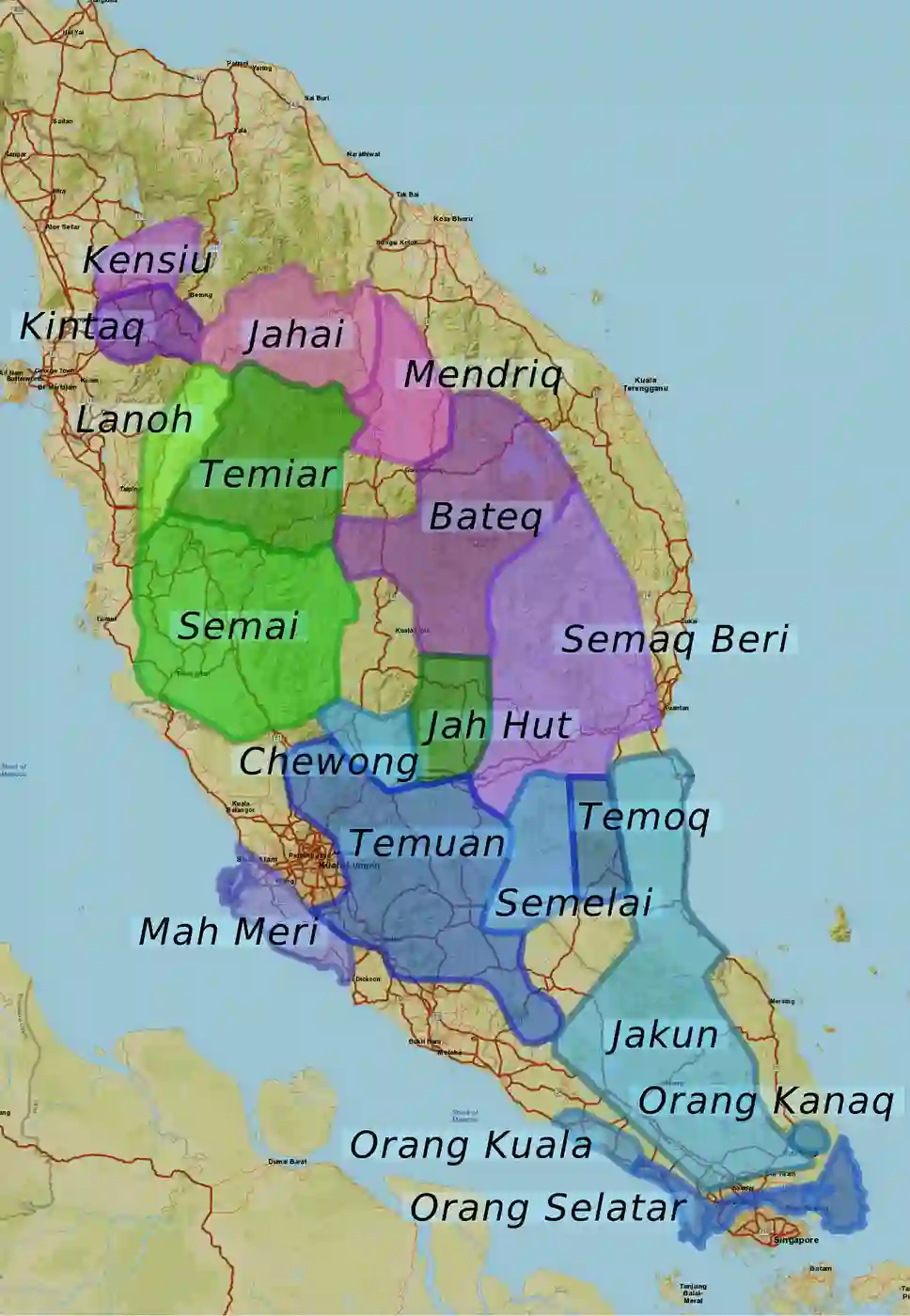

There are some 19 identified indigenous people groups in the Peninsula, which are categorised, linguistically and geographically, into three main groups, those being, the Senoi, the Negrito, and the Proto-Malay. The Senoi group consists of four ethnos, which speak closely related, Senoic languages. The largest of these groups, and of the indigenous peoples as a whole, is the Semai (with a population of over 44,000, as of 2003), followed by the Temiar (population over 26,000). Their communities can be found in the Pahang-Perak mountains (of the Semai) and the Kelantan-Perak mountains (of the Temiar). The two other groups are found neighbouring the Temiars in Perak (the Lanoh) and further south in Pahang (the Jah Hut). The Senoi refer to their home regions largely after the main rivers and not by state names, with such names as, Beter, Slim, Broox, Betis, Perias, or sometimes with the name of the administrative centre, such as Kimaar, Banun, Sindrut, Simpor or Goob.

The Negrito group consists of some six sub-groups of typically nomadic peoples, who are generally darker-skinned, with frizzy hair, are believed to be the oldest dwellers of the land. Their languages are also very closely related to each other, while they have also borrowed from Senoic languages, especially Temiar, wherever they have lived in close contact. The Proto-Malay groups are descended from early Malay (Melayu) migrants to the Peninsula and speak languages related to Malay. The Semai and Temiar people call themselves Sɛnˀơơy, which means, simply, ‘people’. In Semai, the term is enough to mean ‘indigenous people’, but the Temiars say, Sɛnˀơơy sɛŋrơx, to imply the same, or ‘forest people’. The official name adopted by the government to be used for all indigenous groups in West Malaysia is Orang Asli, which means ‘original people’, whereas, the title for indigenous peoples across Malaysia, including Sarawak and Sabah, is Orang Asal, which means ‘people originated’ (from the land).

The Senoi are the indigenous people of the land, inhabiting its plains and mountains long before it was known as the Malay Peninsula, or even Malaya (the name is believed to originate from the ancient Sanskrit name Malayadvipa, found in the Vayu Purana, meaning “mountain island”1). The Senoi are called tribal due to the distinction that stands between each ethno-lingual group, culturally and geographically, and their isolation from the outside world. They are also called forest people due to their traditional lifestyle that is dependent upon the natural resources of the rain forest. While people of the modern world learn everything from textbooks and source their food from the supermarket, the Senoi live by age-old knowledge inherited from their ancestors and they forage for their daily needs from what nature provides.

The Senoi have lived almost completely isolated from the outside world for hundreds, if not thousands, of years, which has been largely due to their location in the upland valleys of the central mountain range. Senoi in the lower areas, and especially on the western side of the watershed, would have made contact with traders more frequently, whereas on the eastern side, in today’s Kelantan state, the Senoi would only have met Malays when they rafted down-river to sell their wares, such as rattan, macaque monkeys, and native rubber. It is also known that lowland Malays in Perak made incursions into the jungle, to locate Senoi villages in order to abduct persons, mostly the Semai in Perak, for slaves. Anthropologists, such as Blagden, ventured into the Senoi areas as early as 1890.

So, although outsiders have known of the Senoi since at least the 1920s, real contact was made only in the 1950s when the British army arrived, to hunt down the Chinese communists who were taking refuge in the dense jungle. The British set a plan into action to gather the Senoi from their remote dwellings and relocate them to safer areas downriver, supplying them well with food in order to win their “hearts and minds”, and thus cutting off the Communist guerrillas from accessible food sources, which the Senoi were planting (and being forced to plant in large areas), as well as intelligence help they could have been providing. The British needed more cooperation from the Senoi, for intelligence on communist movements and as jungle trackers for patrols, in order to win the war (termed the Malaya Emergency). But there were some British colonial officers who did their part to help the Senoi and this is notable with the continued efforts of the flying doctors—a service that was begun after, very tragically, many Senoi died from disease and trauma during the temporary migration.

Such officers and doctors are still remembered today and talked of with much appreciation. Dr Bolton is one of those commonly referred to as a very kind and generous doctor who visited the Senoi, and stories are told of how he flew in by helicopter from the hospital dedicated to OA care at Gombak, to all the interior Posts. The first time when helicopters flew in there was nowhere to land, but when they did the villagers tended to run away for fear. Even when the flying doctors came in, the children ran away to hide (I know a man who remembers doing this) and the doctor would ask, “Where are all your children?” The chieftains and men in their old age today remember meeting Dr Bolton, and they might remember the officer’s name and the soldiers in the scout party they were attached to as volunteers. They formed such close bonds that their British friends even asked them to return to England after the Emergency, although that wasn’t possible. Some Senoi say that Malaysia could not have achieved the peace and security that it enjoys today without their help—their expert jungle knowledge and bravery in confronting communist fighters. Tuan (Sir) Baye was a British District Officer of that era whom they fervently remember.

Two women of the Batek tribe with elaborate face decoration.

Two women of the Batek tribe with elaborate face decoration.

The British saw that the Senoi needed protection from the expanding development of the country, and recommended that the Orang Asli remain separate from main society. Unfortunately, however, the British never recognised the Orang Asli as having the right to rule their own land, or as having the social systems in place to govern themselves efficiently (and in any case, all the Orang Asli ethnic groups were rather separated from each other, geographically, politically, and linguistically). Village head men were appointed, called the Tok Batin (among the Semais) or Tok Penghulu (among the Temiars) who would be the contact man for the authorities. But Senoi culture has never supported having chieftains over the people, but communities always held open discussions, to hear the the counsel of the elders. The Toᵏ halaaᵏ, or ritual adept (similar to a shaman but not a spirit-manipulator as shamans are, but a spirit-invoker) was always revered as the person of authority and his advice through dreams could most often decide matters. These days, the Tok Batins are not exactly treated as having any authority, but only as the go-to man for proposed government projects. The batins still receive salaries, paid once in three months, from the government, which is helpful—but it is not a large sum of money, at only RM200 ($60), and sometimes there’s nothing. Since Malaysia’s independence, over 60 years ago, care for the Senoi and indigenous groups has been held by the Department for Orang Asli Affairs (JHEOA), which has since become the Department for Orang Asli Development (JAKOA).

A Temiar man with blowpipe.

A Temiar man with blowpipe.

The Senoi are essentially hunter-gatherer people who abide by age-old traditions and knowledge of the natural environment they live in and are dependent on. Even though today there are roads (earth roads made by logging companies in most cases, with paved roads only in lowland areas), government schools, clinics, traders who drive in from outside, satellite television, and now free Wifi, the traditional way of life is still well known and well-practiced. This however, is perhaps better said of the upriver Senoi, who still have forest to roam, to collect materials and gather wild fruits or hunt game in, as the lowland Senoi are being pushed more and more into sedentary lifestyle dependent on finding money to survive, since their natural resources have been exhausted or replaced by land development.

It is said that, if the Senoi had no manioc to eat, they would have died out long ago. It has now become one of their staples, along with hill rice, millet and sweetcorn. As swidden farmers, they cut down small areas of the forest and burn the cuttings (often bamboo areas) and plant their crops, often as a community. While one swidden is still young, another one from a previous year is used to harvest food. Women often set off in the morning (or when the basket of tubers at home is used up, at any time of the day) with a home-made woven back-basket to the swidden where they pull up manioc roots, cut the roots from the plant, and load the basket to the full. Manioc roots are baked in the fire embers, or boiled in bamboo (the traditional cooking pot) with any game or fish they caught, or, in these modern days, in an aluminium cooking pot. The swidden would normally use 2-4 acres of land. After the crops were finished, the swidden was left to grow over with new forest, notably bamboo to begin with and later large trees. An old swidden site of over 60 years of non-use would hardly be recognisable today as once having been cultivated. They practiced shifting cultivation in the old days, before the peace was disturbed, relocating every two or three years up and down their river, cutting swiddens at ideal locations, where the land was good for planting and there was easy access to water. Water would be transported to the home by an aqueduct made of bamboo or in bamboo tubes carried by hand.

There is a wide variety of wild animals which the Senoi catch and eat from the hill forest, starting with the favourite, the wild boar, down to smaller animals such as tree shrews, and seasonal creatures such as porcupines, and forest rats, and more coincidental finds, such as snakes, monitor lizards and turtles. Nearly any creature that is found in the forest is food for the Senoi, if they can catch it, and especially those creatures up in trees that can be shot with the blowpipe or that wander along forest animal tracks which can be caught in a trap. They will eat civets, bearcats, slow loris, flying foxes, bats and even jungle cats. Not to mention the many kinds of bird they catch and roast at home—some that taste like lemongrass because of the fruit which it was feeding on, and some which are migratory (wreathed hornbill—a large black bird with a top-serrated white bill) which are shot with a rifle or caught with sticky gum on a high branch. There is a total lack of education for the Senoi about rare and endangered animal species. The Senoi eat these animals just to survive, without realising the importance of many animals to the forest’s ecosystem or knowing the vulnerability of many. But I speak mainly of the Semais here, as the Temiars have many taboos concerning game and there are many animals forbidden for women and children and many animals that they won’t hunt. The Temiars are repulsed by snakes and won’t eat them. The Senoi will also catch young animals and raise them as pets, until they need to be released into the wild again. They often keep wild boar piglets, squirrels, civets, slow loris and even the sun-bear and leopard cats.

A man of the Temuan tribe, in Ulu Langat, Selangor, 2006.

A man of the Temuan tribe, in Ulu Langat, Selangor, 2006.

Traditionally, the Senoi build their homes off the ground on piles, with walls of bamboo, the most readily available building material, and roofs of woven palm branches, all tied together with split rattan vines. A bamboo home would usually last long enough to cultivate a swidden and live off the crops it produced, and by the time the roof had begun to rot it was time to abandon the swidden and move on to start a new one. These days, some homes have zinc roofing, allowing the house to be more permanent. Central to any home was the fire-mound, around which people gathered to eat and talk, and it was the only source of light at night. Sometimes a communal longhouse was built, with compartments for families, each with their own fire place. A meeting hall would be built at each homestead, to host traditional sewang dances, to invoke soul-guides from dreams. Typical to the dance was the music made with bamboo tubes stumped on a log and sometimes with other instruments such as the bamboo guitar, nose flute and mouth harp. The participants decorated their faces with paints and wore headbands woven from palm leaves. Some of their spirit-invoking ceremonies were conducted in complete darkness, lasting all night, and were led by an adept who would invited the souls he had met in his dreams to approach the hall and give their blessing.

Dreaming is an integral part of Senoi culture, and the entire folklore of the Senoi originates from dreams of those who could find souls who would guide them and teach them. These dream guides, said to be the souls of animals and other entities, including mountains, would provide the dreamer with protection from harm and from evil roaming souls, along with a flowing virtue that could be used in healing rituals. They were also respected by the community as the wise men and women and would be looked to to sort out any dispute or to know where the kin-group should move to next or the right time to cut or burn a swidden. Each kin-group, or ancestral group, else known as a ramage, of families descended from a common ancestor, would have their own small river valley, demarcated by the ridge lines on each side, up to the river sources or mountain ridge. Their old swiddens and planted trees and even resources that they collected from, such as roofing palms and wild durian trees, were considered the inherited possessions of the kin-group. People of neighbouring kin-groups would not encroach on the river valley or hunt or collect resources in it, respecting the rights of the ancestral heirs. This custom has enabled the Senoi to survive for a few millennia, as each kin-group can provide for its own from the natural resources around. Nowadays, ever since the army forbade them to wander away from the forts during the Insurgency, the Senoi are settled in more permanent locations and one may find their villages dotted along the main river of a large river valley, or sometimes up a tributary river.

A Semai man with nose quill.

A Semai man with nose quill.

Even though the Senoi are indeed one of the oldest ethnic groups of the Peninsula, possessing a wealth of inherited knowledge of the environment, natural plant species and a tested and enduring social system with ancient rites and moral guidelines, they are still deemed backward and unimportant by the mainstream population. Such attitude has only led to the assumption that the Senoi are a hindrance to development and they need to leave behind their traditional ways and integrate into modern society, by means of conversion to religions and conforming to popular culture. In the 1950s, the Senoi still wore their loin cloth made of tree bark, they trod the paths bare foot, pierced the septum of the nose with a porcupine quill and carried little more than a basket, a blowpipe and a blow-dart quiver. There were no roads and the only mode of transport was rafting down the river and walking back on foot, along ancient pathways in the forest. Their isolation meant that they dwelt in tranquility, only needing to adjust themselves to their own social framework and to the dictates of nature all around them. But times change, and they were not left alone. The incursion of the Chinese and the British, along with Malay and Gurkha soldiers, with machine guns and iron bombs pounding the swiddens, saw that their peaceful existence was turned upside down. Ever since they were forcibly relocated, and even after returning again to their former homelands, the life of the Senoi people has been confronted with many new challenges, such as logging companies destroying their forest and causing animals to flee and rivers to sand up, and religious groups campaigning for their ideals, persuading villagers with food hand-outs and empty promises. Even political groups venture in campaigning for things the Senoi do not fully benefit from.

The Senoi are a peaceable people and they always desist from direct confrontation. This means that when someone from outside the community speaks or acts abusively, or gives a rip off price using ‘locked’ weighing scales, they will usually just watch and stay silent. According to their belief, such abusers will one day meet with ill fate, as a result of committing ‘sin’ against them. Among themselves, they do not enter into physical aggression, but they do curse one another verbally, and those who know magic will even cast harmful spells on others. In the long past, the Senoi were known to blowpipe serious abusers and their blow-dart poison proved extremely lethal. There is a legend with the Semai telling of a man and his nephew who were forced to lead a Malay raiding party to their village and they tricked them and led them the wrong way. When the Malays found out they were about to kill the two Semais, so they were forced to use their magic and fly off into the trees, from where they blowpiped the whole party. But the old man was stabbed in the process and died. The Temiars also did not refrain from using their blowpipes on some Chinese abusers who were attempting to molest their women at a relocation encampment, in the 1960s.

Page 2 coming soon !!

Footnotes

-

This information was found on a popular online encyclopedia! Hidden within today’s “Malaysia” is the ancient name Malaya, the name derived from the Indian merchants who regularly visited the “mountain island” across the sea. The name Malaya is therefore not synonymous with the ethnonym Melayu, which is derived from a river’s name in Sumatra (from me-laju, ‘running swiftly’) and thus it is illogical to call Malaya anything like Melayu Land. Anyone born in Malaya (obviously to a Malayan parent) would then be a Malay person (or better, a Malayan), including the indigenous people (in the eyes of foreigners, at least), the Melayu, and any other ethnic group. The indigenous peoples, however, wouldn’t have even known of the name Malaya, it being derived from a foreign language, and would only be familiar with regional names of rivers. It is possible they called their land by the name Tanjɔɔx, meaning peninsula, but they would have needed a larger geographical knowledge of just river valleys to have understood such a concept. ↩